In Boston, just across the river from HubSpot’s headquarters, St. Patrick’s Day is kind of a big deal. There’s a parade. There’s a special breakfast for the who’s-who of local government. There are green bagels. And there’s a lot of beer.

We like to think of that as a very traditionally Bostonian way of celebrating St. Patrick’s Day. And we’re not alone -- in Chicago, for example, they dye the river green. But we’ve got news. That word, “tradition”? We hate to break it to you, but today’s celebrations of St. Patrick’s Day are, well, far from traditional.

And like so many other holidays, the modern perspective and observance of St. Patrick’s Day was shaped in some part by -- you guessed it -- marketing. But what did it used to look like, and how did it get to where it is today?

Grab your four-leaf clover, because you’re in luck. (Sorry, we couldn’t help ourselves.) We’re taking you on a trip back in time to figure out just where St. Patrick’s Day began.

How St. Patrick's Day Celebrations Were Shaped by Marketing

Who Was Saint Patrick, and Why Do We Celebrate Him?

Source: History.com

Source: History.com

The Man

To really trace the roots of St. Patrick’s Day, it’s important to understand its name. Yes, it’s named for a person -- Saint Patrick himself -- who actually wasn’t even of Irish descent. According to History.com, he was actually born in 390 A.D., in Britain to a Christian deacon father. It’s rumored that he assumed that role for its tax incentives, and not for religious reasons. In fact, some speculate that Saint Patrick wasn’t raised with much religion at all.

Interestingly enough, it was being kidnapped in his teen years and held captive by Irish raiders that began Saint Patrick’s journey to, well, sainthood. Much of that captivity was spent in isolation from other people, which allegedly caused Patrick to turn to spiritual thoughts for guidance and comfort. After six years as a prisoner, he escaped back to Britain, and eventually studied to become a priest.

After he was ordained, he was sent on a mission back to Ireland to begin spreading and converting the population to Christianity. And according to National Geographic, it didn’t go so well -- “he was constantly beaten by thugs, harassed by the Irish royalty, and admonished by his British superiors,” and he was “largely forgotten” after his death in 461 A.D., which is estimated to have taken place on March 17, the day observed as St. Patrick’s Day.

The Myth

But later, people started to create folklore around Saint Patrick. It’s not clear when these legends came to fruition, but you might be familiar with some of them -- tales of him banishing all snakes from Ireland, for example, which are the stories that eventually led to him being “honored as the patron saint of Ireland” -- hence the name, Saint Patrick.

Still, the celebrations of him within that particular nation remained pretty low-key until the 20th century, prior to which March 17th was mostly observed with a mention of it by priests, and a feast enjoyed by families. Plus, there remains conflicting information about his life and the exact dates of its major events.

In fact, the celebrations really began right here -- in Boston.

What the Earliest Celebrations Looked Like

Coming to America

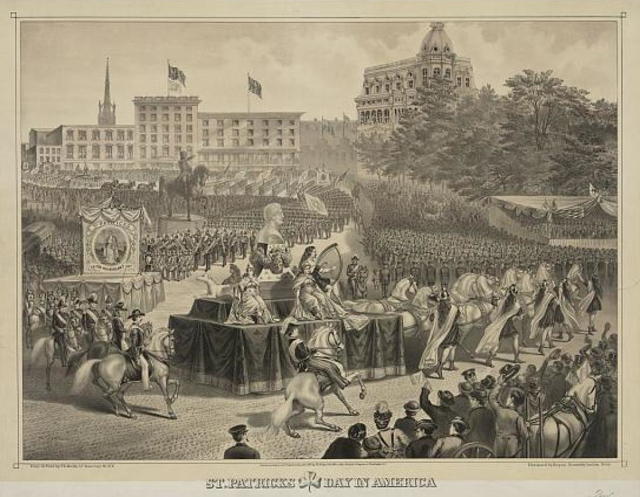

According to Time, the inaugural celebration of St. Patrick’s Day took place in 1737, in the form of “a group of elite Irish men” in Boston gathering for a dinner dedicated to “the Irish saint,” who one might assume was Patrick himself. Less than 30 years later, parades began in New York, with Irish-American members of the U.S. military marching to honor Saint Patrick “with Fifes and Drums.”

Source: Ephemeral New York

Source: Ephemeral New York

Both of these events have led many to speculate that how we view St. Patrick’s Day today was largely an American invention, as many of the traditions we still continue to honor -- including the New York City parade, which has grown by leaps and bounds in the past 251 years -- were started by Irish-American immigrants. And as Irish immigration increased exponentially during the 1800s, the celebrations grew in kind, in large part to combat stereotypes that this incoming population was “drunken, violent, criminalized, and diseased.”

Irish-Americans wanted a way to illustrate that they were wholesome people -- that they paid tribute to their natively religious roots with an observation of the patron saint, but that they also embraced life in America, by creating these traditions on new land. And that population was the most concentrated in Boston, Chicago, and New York -- which might be why we today see the grandest celebrations in those cities. That began when Irish-Americans continued to face opposition by others, despite the aforementioned best efforts. The parades got bigger and occupied less localized venues, sending the message, "we’re 'not going anywhere.'"

Meanwhile, in Ireland …

Eventually, around the 1920s, Ireland began to observe St. Patrick’s Day celebrations beyond church mentions and family meals. Not entirely unlike New York, it started with military parades in Dublin, but they weren’t exactly festive -- “the day was rather somber,” writes Mike Cronin, with “mass in the morning [and] the military parade at noon.” And, until the 1960s, there was no drinking -- before then, bars in Ireland were closed on St. Patrick’s Day.

But in that country, at least, the holiday saw a real turning point in 1996, with the very first instance of the St. Patrick’s Festival in Dublin: A four-to-five-day festival (which began as just one day) of music, parades, and other revelry. This year’s edition of the festival just kicked off yesterday and, today, brands across numerous nations -- Ireland and the U.S. alike -- are capitalizing on the celebration.

Source: St. Patrick’s Festival

Source: St. Patrick’s Festival

We’ll get to that in a bit. First, let’s look at how some other St. Patrick’s Day traditions got started.

Why Green?

It all began with a song, “The Wearing of the Green.” It dates back to 1798, when it was said to be written as a tribute to Irish Rebellion fighters, and has been repurposed many times since. The phrase in this post's title, too, has ties to Irish fighters -- "Erin Go Bragh," which is traditionally spelled "Éirinn go Brách," means "Ireland forever," or Ireland "till doomsday."

The most notable version of "The Wearing of the Green" is thought to be the one written and performed by Dion Boucicault in 1864 for the play Arragh na Pogue, or The Wicklow Wedding. And while there’s some controversy surrounding this theory, many believe that’s where the tradition of wearing (and consuming) all things green on St. Patrick’s Day is rooted -- though it’s an act of gross misinterpretation, since the lyrics were actually meant to encourage the wearing of a green shamrock, a symbol of the Holy Trinity. In reality, the original color association with St. Patrick’s Day was blue.

Source: Free Printable Greeting Cards

Source: Free Printable Greeting Cards

But what of that shamrock, yet another item that’s come to be so strongly associated with contemporary interpretations of St. Patrick’s Day? Well, that goes back, in part, to “The Wearing of the Green” lyrics. Have a look:

She's the most distressful country that ever yet was seen

For they're hanging men and women there for Wearing of the Green.”

Those lyrics actually allude to the fact that, during the Irish Rebellion, wearing a shamrock was an offense punishable by death -- and doing so came to be seen as a brave act of rebellion and loyalty to one’s Irish roots.

It could be why, today, wearing green on March 17th -- often adorned with shamrock shapes -- is loosely seen as an act of pride for all things Irish. In fact, you may have heard the phrase, “Everyone is Irish on St. Patrick's Day,” which has been largely perpetuated by high-profile Irish brands, like Guinness.

That’s one particularly outstanding example of how St. Patrick’s Day is now highly commercial -- it’s not just American brands that are leveraging it for marketing purposes. And believe it or not, there are many indicators that it began with this accidental tradition of “the wearing of the green.”

When It Started to Get Commercial

It’s the Shamrocks, Again

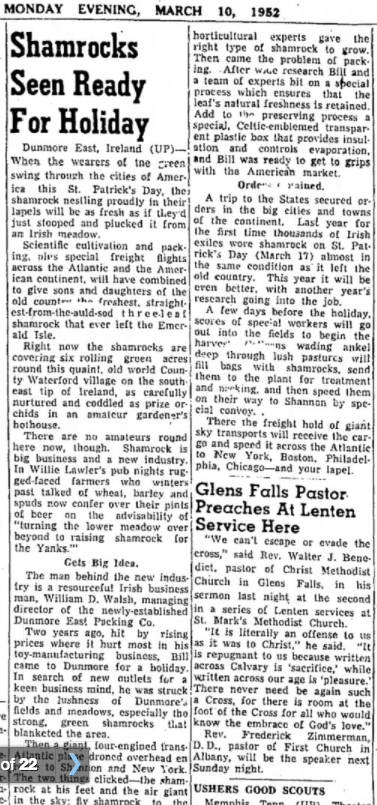

There were several pivotal moments in the history of St. Patrick’s Day that could be pointed to as the beginning of its commercialization -- events like the first St. Patrick’s Festival in Dublin, or the first parade in the U.S. Indeed, it seems that the commercialization did begin stateside in 1952, when Irish ambassador John Joseph Hearne delivered a box of shamrocks intended for then-President Harry Truman. It’s since become an annual tradition.

But it wasn’t just the start of tradition. What used to be a symbol of Irish pride and rebellion was now being gifted to U.S. officials from Irish ones. It signaled the same efforts that Irish immigrants were trying to make when their small, localized St. Patrick’s Day celebrations first began: Honoring native traditions, while also embracing the U.S. by sharing them. It was an effort to establish and strengthen “pro-Western credentials with Washington” -- a city where, at the time, there was little observance of St. Patrick’s Day -- said Michael Kennedy, executive editor of Documents on Irish Foreign Policy in an interview with CNN.

In a way, it could be said that Americans embraced this Irish tradition in return -- but not without putting its own commercial spin on things. The same year as that unintentionally monumental shamrock delivery, Pan American Airlines promoted its first direct flight from Shannon, Ireland to New York by flying 100,000 native shamrocks to be handed out to those marching in the New York parade.

Source: Newspapers.com

Source: Newspapers.com

In other words, at that point, the shamrock had made its way to the U.S., and businesses and consumers alike couldn’t get enough of it. "The marketing of 'real' shamrock was...part of the commercialization of St. Patrick's Day," writes Cronin in his book The Wearing of the Green. "More frequently, the image or symbol of the shamrock was employed artistically -- adorning souvenirs, advertisements, decorations, greeting cards and clothing."

Most of all, the celebration of St. Patrick’s Day in the U.S. now extended far beyond the Irish-American population. With the shamrock’s permeation into popular culture, non-Irish individuals also began to take part in the holiday’s observance, adapting it as their own until it got to where it is today -- green rivers, green beer, and a lot of shiny green accessories. As we said, and as is often claimed: “Everyone is Irish on St. Patrick's Day.”

Today's St. Patrick's Day Celebration

So, what are your plans for St. Patrick’s Day? Does it involve any of the aforementioned revelry and/or accompanying green adornments? Will you be feasting on corned beef and cabbage -- a dish largely unconsumed in Ireland? Now you know how we got here.

It’s been quite a few years since I’ve donned my own glittery, shamrock-shaped earrings, or worn beads a shade of metallic green while partaking in a March 17th pub crawl. But now I’m aware that none of this has to do with the person for whom the holiday is named: Saint Patrick. And as a marketer, I can’t be too angry about it -- after all, many holidays in the U.S. have evolved in a similarly commercial fashion. Just last month, we discussed how that took place with Valentine’s Day, which was also originally established in observance of a saint.

But we will ask that, as you go forth and consume a green milkshake today, to at least be aware of the history that made it possible. Erin Go Bragh -- and as the saying goes, may you have a world of wishes at your command.

How does your brand observe St. Patrick’s Day? Let us know in the comments.

from HubSpot Marketing Blog https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/st-patricks-day-marketing

No comments:

Post a Comment